This post was written at the invitation of Alison Jeffers and Gerri Moriarty, whose book, Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art: The British Community Arts Movement has just been published. It first appeared on their project website, and minor revisions have been made in this version: texts, like history, are restless.

Making history

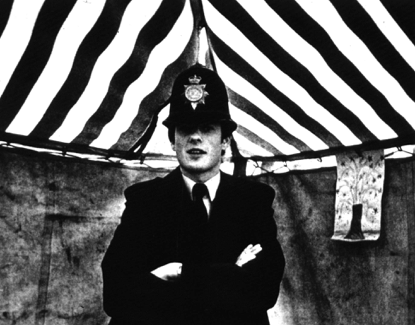

The early years of community art in Britain are becoming history. The people involved are in their sixties or older and, although many are still engaged in arts practice, it’s natural to look back and reflect on what happened – especially if you once hoped to change the world. The testimony of that generation is being recorded in films and for websites. Attics yield old photos, posters, sketches, plans, press cuttings and reports for the archives of Jubilee Arts, See Red and others. Those projects have gone but others, including City Arts and Mid Pennine Arts, are celebrating 40 or even 50 years of work. Community art has survived better than many expected, albeit by adapting to a changing world. And now the first academic histories are appearing, including Alison Jeffers and Gerri Moriarty’s Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art (2017)

For anyone who took part in these events, all this must bring a degree of nostalgia. It’s nice to be reminded of people you knew, in the time of murals, typewriters and Letraset, tenants’ associations and community development workers. It is interesting to look back, but what’s important is the history being made of it. What story is told, by whom and from what perspective? Do I believe it? Above all, what use does it serve? On such questions, my interest is not nostalgic, even if the subject is now remote. Interpretations of the past matter because they shape how we think and act today.

Take the critical question of whether the community art movement ‘failed’. The idea that it did seems widespread – I’ve read it twice recently – and it is often based on the arguments made by Owen Kelly in Storming the Citadels. I remember the book’s publication, in the grim year of 1984, when the Thatcher revolution had brought deindustrialisation, unemployment, civil unrest, the Falklands War and nuclear confrontation with the USSR. The progressive defences of the post-war era were being overrun by neoliberalism’s rising tide (although no one yet used that term). Kelly’s book spoke to that world and I shared its commitment to cultural democracy.

Still, it seemed a long way from the everyday realities of life as a sole community arts worker on a Midlands council estate. In Kelly’s 1984 analysis, the radical potential of community art had been compromised by theoretical and political inconsistency, linked to the acceptance of public funds. It was a powerful argument, but I had never thought that ‘a revolutionary programme aimed at the establishment of cultural democracy’ (Kelly 1984: 137) was possible or, perhaps, consistent with its own philosophy. What political weight did a few hundred community artists truly have when the power of the trade union movement could not prevent deindustrialisation? Political and economic change since the 1980s has been historic, international and largely against the ideas of the first generation of community artists. But there was little they could do to affect it, even in 1984, when the ascendancy of neoliberalism was not yet assured.

In any case, as Owen Kelly recognised in 1984, the community art movement would not or could not unite behind a revolutionary programme because there was no common understanding of community art’s radical potential and purpose among the people involved. They had a wide range of ideas, commitments and reasons for doing what they did, and they worked with communities with equally diverse experiences and interests. In a cultural democracy worth the name, every one of these people – professional and non-professional artists – had the right to argue for and pursue their vision.

You get a sense of that diversity from the other key book published about community art in its early years, Su Braden’s Artists & People. Published in 1978, it is less often cited than Kelly’s, which is a pity because it is a nuanced and challenging account of community art’s first decade. Braden is critically engaged by the whole spectrum of ideas, motivations and achievements in community art. Her vision is as radical as Kelly’s – they share a disdain for cultural imperialism – but her focus was on how art, not politics, might be changing the world. Braden saw the problems raised by the emergence of the community arts movement, but she also understood the depth of the change happening to art in society that had caused its emergence. Above all, she valued the role played in that by

‘those artists and groups who have the rare talent, stamina and perception to propel themselves out of the tired, brittle, formalistic atmosphere of the art world to work in a variety of community contexts. This is where the future life of the arts will be judged.’ (Braden 1978: 181)

The French Revolution ended, for many people, with Napoleon’s seizure of power In 1799. What no one could see at the time was how its new ideas would reshape the world in far more profound ways than which system of government would briefly rule in one country. In 1984, it looked as if any revolutionary potential the community art movement had once nurtured was vanishing. Today, as Owen Kelly reflects in his contribution to Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art, it is clearer that

The impetus that fuelled the original community arts activists did not die, but rather lives on in a number of surprising ways. (Kelly 2017: 223)

I share that assessment, not the earlier one. The British community art movement (1968-1986) was as much a symptom as a cause of change; as such, its existence was always more important than its achievements. It was the current expression of a struggle for cultural equality (now reimagined as cultural democracy) that has been fought since the Enlightenment – and probably not even the most successful. That struggle is slowly, often painfully but, I believe, steadily being won because the social, political, economic and technological conditions favour its success. Seeing it in those terms, rather than as another romantic failure of radicalism, is empowering. It also makes clear the need to continue the struggle.

As I approach my sixties, I too have been thinking and writing about the history of community art, but I’ve realised that I don’t care about the past as much as I thought I did. It interests me, of course, and it’s a pleasure to read this new book. It’s a valuable gathering of voices and evidence about a field that is often misunderstood, but whose influence on cultural policy and practice has been profound. Bringing Owen Kelly’s current thinking into the discourse is just one of its many gifts, and I will continue to read and learn from it. At the same time, I feel that what I lived through is now history, like the history I inherited – Jennie Lee’s White Paper, Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace, the founding of the Worker’s Educational Association and the rest. Once I’ve organised my own thinking about it, I’m content to let it pass.

I want to learn about tomorrow’s history. It’s the people who are adapting and renewing community art for the 2020s whose work excites me. They don’t think like me. They weren’t shaped by the same events. They don’t know (or care) about my history – and I couldn’t be happier. The work I see them doing is radical, urgent, brave, imaginative and beautiful. It’s often far better than anything I ever did. Sometimes I don’t understand or agree with their choices, but it doesn’t matter. They are doing what makes sense to them, and their right to do that is what I’ve always worked for. This is how the struggle for cultural democracy is being fought now, and it’s brilliant.

They are writing history, in the best way any of us can. By making it.

It is noh mistery

Wi making history

It is noh mistery

Wi winnin’ victory

Linton Kwesi Johnson (Johnson 2002:63)

References

Braden, S., 1978, Artists and People, London.

Johnson, L. K., 2002, Mi Revalueshanary Fren, New York

Kelly, O., 1984, Community, Art and the State: Storming the Citadels, London.

Kelly, O., 2017, ‘Cultural Democracy: Developing Technologies and Dividuality’, in Jeffers, A., & Moriarty, G., eds. 2017, Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art: The British Community Arts Movement, London.

Jeffers, A., & Moriarty, G., eds. 2017, Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art: The British Community Arts Movement, London

Responses

Hi François- I just added your blog to my new FB group- where I had posted a link to this book. I am giving a talk at the next NCECA ceramic conference in USA in March and my theme is activating ceramic artists to engage in more ceramic focused community art projects. Thanks for all your great work the blog and continued commitment to community arts.. I’m hoping to rally more troops for the cause.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sharon, Thanks for your encouraging words; I’m glad you like the blog. In terms of ceramics and community art, did I mention the work of the artists at Airspace Gallery? Check it out if you don’t know it: I think you’ll be interested: http://www.airspacegallery.org/index.php/projects/the_spode_rose_garden

LikeLike