The Light Ships is about community, the feelings and commitments we freely offer each other, unconnected with kin- or friendship, though it often embraces both. I’ve been thinking about community throughout my working life and I’m still discovering its meanings, power and value. I’ve seen it everywhere—in the suburbs of Sofia, in post-industrial Gateshead, in rural Kyrgyzstan, in Barcelona and Tokyo, Uist, Kaunas and Ouagadougou. I’m wary of claims to universalism, especially in culture, but experience has shown me that almost everyone wants to feel part of a community, in one way or another, and that many want to invest themselves in nurturing it.

And it does take investment. Communities are living networks of relationships, constantly shifting like the murmurations of starlings, sometimes stronger, sometimes weaker, sometimes falling apart. They take many forms and vary in scale from a handful of people to nations, and now global communities; in The Empathic Civilisation, Jeremy Rifkin argues that unless humans can extend empathy to all life, our survival is at risk. Community, like culture, may be considered a good to the extent that is is empowering: what people do with that power is not necessarily good. Community can become oppressive to their own members and to outsiders, just as culture can be used to dominate, exclude and exploit.

One reason I have, until now, continued to use the term ‘community art’ to describe my work is because I’m interested in its ability to create community among a group of people—temporary and porous community, chosen and shared, and full of distinct potential. As I wrote in Use or Ornament? (1997), much of what we gain from participating in the arts is associated with the act of participation, not culture, and participation is the energy that creates community.

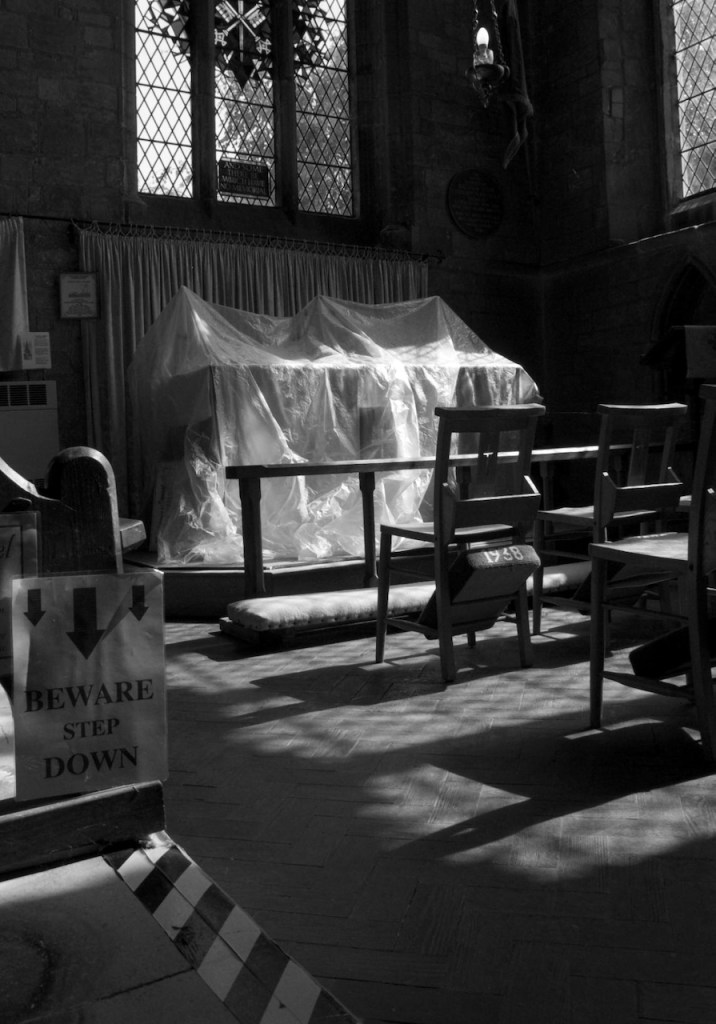

The Light Ships explored some of those ideas through the voices of people living in a dozen Lincolnshire villages. It was a response to a commission by Transported, who wanted to reach out to communities in Boston and South Holland. When I visited some of the villages, it struck me that the only thing they had in common was a church – medieval, often huge and full of beauty and interest.It was often the only shared space, apart from a functional village hall, and although few attended regular services, the church remained a focus for important moments in life, from weddings to funerals, and community events. It was also full of art – from sculpture, painting and glass that would be in a museum if it were not in the church, to the painting exhibitions, concerts and flower shows of contemporary cultural life.

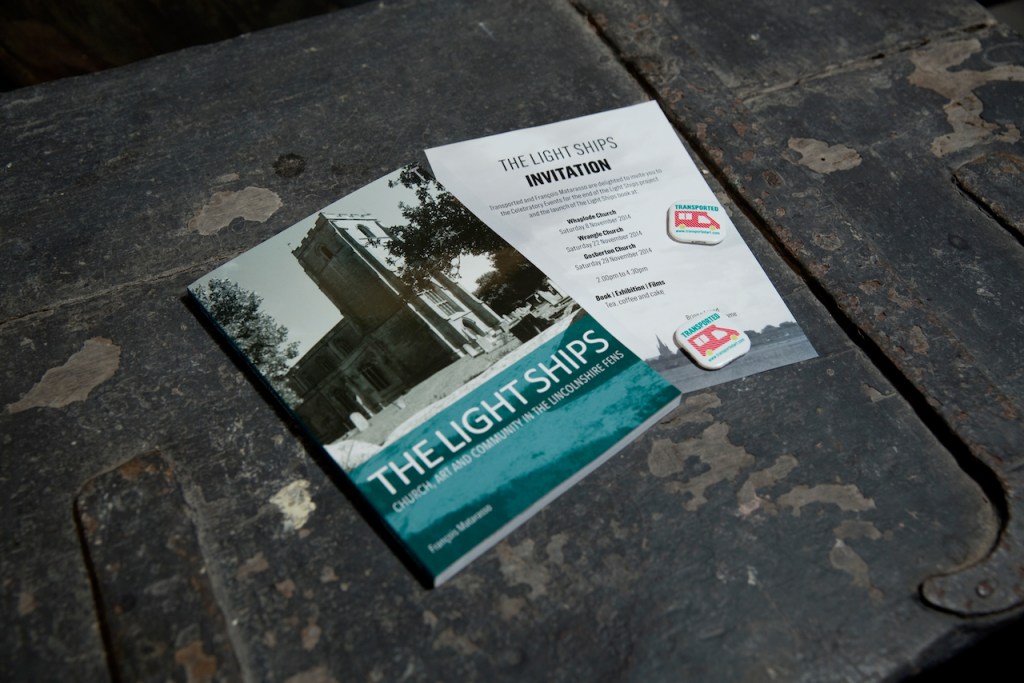

So I spent the lovely summer of 2014 meeting people associated with village churches and learning about what they meant. I recorded our conversations and edited a multi-vocal text in which people from different communities shared their thoughts and experiences without commentary. I wrote two rather poetic essays, one to introduce the book, the other to reflect on what had been said. And I included photographs of the people and the buildings, to illuminate both their cultural riches and the ambiguity of their situation at a time of social changed. There were three events, with exhibitions and performances, to celebrate the publication of the books, and 100 copies were given to each church for sale to visitors.

The Light Ships was also a personal tribute to some of the writers and artists through whom I learned to look at buildings, including Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, Alec Clifton-Taylor and especially the photographer Edwin Smith, who produced a series of books for Thames and Hudson in the 1950s and 1960s, with text by his wife, Olive Cook. I had become friends with Olive, late in her life, and The Light Ships is dedicated to her.

The Light Ships has little to do with me personally, but it is close to my heart. Two years after its publication, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. In Boston and South Holland, the districts where I worked on the project, three quarters of the vote was for withdrawal. Benedict Anderson says that all community is imagined, and many of those I had met imagined a community in which I do not feel at home. In my imagination is the England that welcomed Nikolaus Pevsner as refugee and enabled him to create an intellectual monument to his adopted country, a tolerant, phlegmatic, decent place, whose people volunteer to help their neighbours and build community. This is the genius loci of The Light Ships, which may be why the book has a somewhat elegiac tone. Or perhaps it’s just nostalgic—dated and out of time. Either way, Brexit was a decisive moment: I felt compelled to choose my community.