What became Regular Marvels emerged in the dying years of New Labour (2008-10). It was a period of crisis—the collapse of neoliberal finance brought recession, austerity and the rise of reactionary politics we’re still dealing with. History is experienced by individuals and for me these global events echoed in my own crisis. Its obvious manifestation, among personal griefs and uncertainties, was a difficulty in finding work, or even knowing what I should be doing. Turning fifty, I had sharp questions about the meaning and value of that work—questions that have returned as I approach 65, bearing other losses.

Two ideas preoccupied me then. The first was that I had been drawn into writing about community art in ways that risked excluding the very people whose work and lives I documented. Making the case for cultural democracy in policy and academic circles had led me to adopt the ideas, values, methods and language I’d originally set out to challenge. Without realising it, I’d started back on the wrong side of the line.

I wanted to write about people’s everyday cultural lives in ways that had meaning for them, to write with rigour but without perpetuating academic and political power structures.

The second idea was that art should be central to my process of inquiry. The belief that art is a language and a way of creating knowledge had led me into community art and yet now I was writing about it as if it was irrelevant to research. I wanted visual art to be as important as words in what I was doing. The solution I found was to imagine short books that combined the resources of sociology, literature and art to highlight under-valued aspects of cultural life.

Between 2010 and 2015, in the grim years of coalition government, I worked on five such projects, each beginning in a conversation with an arts organisation of a foundation. I liked them all, though they are very different and each has its own qualities and flaws. None was wholly successful, I think, but they’re all interesting experiments. It’s a bit disappointing that they have been ignored by academics and policy-makers but not surprising. Lack of attention has always been the easiest way for power to protect itself from dissenting voices. If you break the rules, you have to expect those who make them to ignore you.

‘Winter Fires’ was the second of the books to be published, in the autumn of 2012. Seeing the steady rise over the years in participatory art work with older people, I worried that only one side of the experience of ageing was being recognised—that of diminishment, loss and need. I knew that older people are artists too and have as much to offer as anyone. So, with the generous support of the Baring Foundation, I set out to tell that story, meeting older artists across the UK and Northern Ireland. They fell into three broad groups: professionals who were still creating after the age of retirement; people whose youthful love of art had been blocked by the need to work; and people who had come to art for the first time in retirement, often using age as their subject Their lives were rich in experience, artistic creativity and commitment. Above all, artisting, to use the word I invented in the book, gave them agency at a time when physical, economic, social and emotional losses can seem only to diminish our freedoms and our selves.

‘Art does have a further capacity that is quite particular to itself. It allows the artist, professional or amateur, committed or impulsive, to act in the world. By creating something that did not exist she makes an event that changes reality, however slightly, and gains agency in her own existence. She expresses something of the unique nature of that existence and in doing so becomes a subject, not only an object.’

François Matarasso, ‘Winter Fires, Art and Agency in Old Age’, Baring Foundation 2012

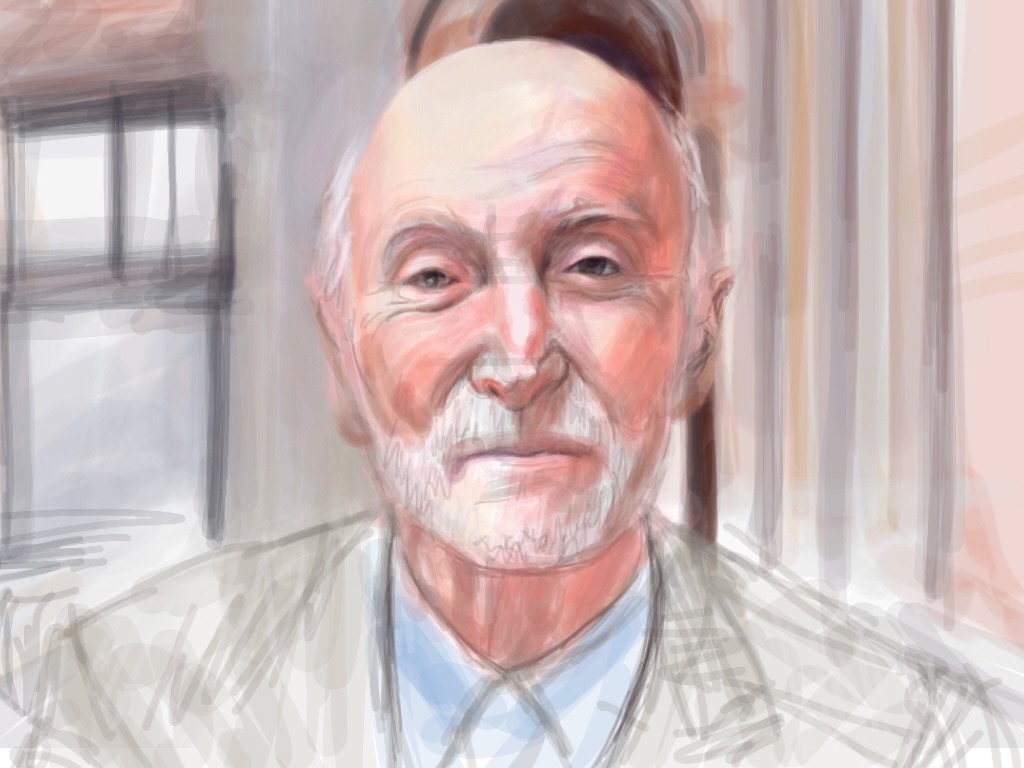

The book included portraits of the people I met, made on an iPad by my old friend Mik Godley. Mik has spent much of the past 25 years investigating his family connections with Silesia and the wartime events that ended with the region being transferred from Germany to Poland. Much of his painting has involved working from found images on the Internet, so it was natural to ask him to work from photographs I took of the people I met. The results tell the same story as the text, but in another language.

When I met the people whose lives are documented in Winter Fires, I was aware of getting older, but I was still young enough to see them as different to myself. I think that shows in the text, despite my efforts of empathy and imagination. Now, I’ve reached the stage of life many of them were at, and it’s the young who seem different.

I believe that the argument of Winter Fires is true: the practice of art gives us agency, even when so many of the powers we once had have weakened or gone. My mother, at 94, still writes strong, moving poetry.

We cannot know what is coming but as long as I can use words to make sense of it, I will be me.

- You can download Winter Fires as a PDF here. If you’d like a free print copy, please contact the Baring Foundation to see if there are any left.

Response to “Searching for a direction: Regular Marvels, Part 1, ‘Winter Fires’”

[…] Previous […]

LikeLike