‘A Fun Palace is not a fete. It’s not about coming along and having a lovely time. It’s not audience development. It’s saying to everybody—you can do this; you already do this. You are allowed to make art and science.’

Stella Duffy

Having fun

Willmer House in Farnham is a dominant building. Its three tall stories each present five windows to the street, except at ground level where the central bay is occupied by the front door. This is Surrey, so the materials are warm red brick and white woodwork. When it was built, in 1718, the house must have seemed a very palace to the farmers and labourers coming along West Street to market, as, no doubt, the gentleman who paid for it intended. Architecture has always been a good way to express status. In 1961, Willmer House became the Museum of Farnham under the management of the Town Council. In the democratising spirit of the age, the house became a small palace of culture, dedicated to passing on knowledge of local history to the descendants of those farmers and labourers.

Willmer House in Farnham is a dominant building. Its three tall stories each present five windows to the street, except at ground level where the central bay is occupied by the front door. This is Surrey, so the materials are warm red brick and white woodwork. When it was built, in 1718, the house must have seemed a very palace to the farmers and labourers coming along West Street to market, as, no doubt, the gentleman who paid for it intended. Architecture has always been a good way to express status. In 1961, Willmer House became the Museum of Farnham under the management of the Town Council. In the democratising spirit of the age, the house became a small palace of culture, dedicated to passing on knowledge of local history to the descendants of those farmers and labourers.

That promise can be felt in the friendly welcome when I walk in one sunny October afternoon in 2016. No one seems to mind that I’ve not come for the collection but to visit the Fun Palace camping in the garden. The Museum is hosting one of 292 events taking place this weekend, in libraries, schools and other venues across Britain and several other countries. The Farnham group, started three years ago by Carine Osmont and Alex Mendonca, has been given the run of the museum’s education space for the afternoon.

A low glass and timber building stands at the end of the garden. So much is going on that it has spilled onto the verandas where children are making hand prints while an artist invites visitors to add personal traces to a map of local culture. Indoors, Farnham Art and Design Education Group are drawing the cosmos, while the local Amnesty International group gathers signatures for a petition about protecting refugees. People sit at tables trying their hand with clay or a plastic melting tool; lots of families, children lost in experiments while parents sometimes take a little persuading. Carine and Alex flit from one activity to another, welcoming new arrivals, answering questions and offering cups of tea.

Later, I listen to a talk about Joan Littlewood, the radical theatre director whose vision of a Fun Palace inspired all this activity. Christine Jackson, who worked with Littlewood in the 1960s, shares tales of community work and cultural activism in East London. She recalls a continuing struggle for recognition but creative freedom too, when no one is interested in you. I glimpse a world in which people do things because they want to, not to deliver a plan or meet a target. And if that includes trying to build a hovercraft, why not? At worst, people will find out that it’s beyond them, but the journey will be rewarding. It is empowering to learn that the goal you set yourself is not actually the goal you want: you know what to do next. Then and now, the Fun Palace encourages people to feel comfortable at the edge of competence because it’s there we find our next selves. In art, the step beyond that seems so frightening turns out to be all right, exhilarating even. And that is a great discovery.

Conventional education programmes aim to interest people in an existing cultural offer—in stories, values and interpretations that those making the offer have long mastered. So the relationship is inevitably unequal. The expertise is all on one side because there is no real recognition that other knowledge or sense-making exists. This is an idea of culture as transmission and, though educators can be good listeners, the learners cannot change stories, values and interpretations seen as factual by those presenting them. Knowledge and skill are great things: all human life depends on them. Teaching is equally vital, and, often, the best thing we can do is be quiet and pay attention.

But culture, although full of facts, is not itself factual. It is a fact that William Cobbett was born in Farnham in 1763 and that he became an influential writer, but there is nothing factual about the meaning of his work to a reader. Like most of what is important in culture, that is a judgement. What is more, it’s important because it is a judgement. We make better judgements when we have knowledge, it’s true, but also when we have learned how to weigh evidence, test claims and trust our own experience. And then we might find that judgement is not the point after all. What matters is responding, as truthfully as we can, to other people’s truthful responses to experience. Being open to our own and other people’s intersecting understanding of the mystery of living—that is exhilarating, and nowhere is it more important—or easier—than in art. We must have the chance to learn about art but we must also have, as Fun Palaces argue, the chance to make it ourselves. We might learn something else than by being quiet and paying attention.

‘Fun Palaces instils creative power in everybody. It doesn’t make arts and science something we read or watch but something we make and do. It’s collaborative and inclusive, bond-building and boundary-smashing.’

Farnham Fun Palace reminded me how creativity springs also from desire—something artists know in their own work but do not always remember when they open that work to others. We all have to adapt our desires to reality, when we discover that we can’t or don’t after all want to build a hovercraft. But that is the essence of learning: me in the world, exercising agency and discovering its limits, consequences and rewards.

Inventing fun

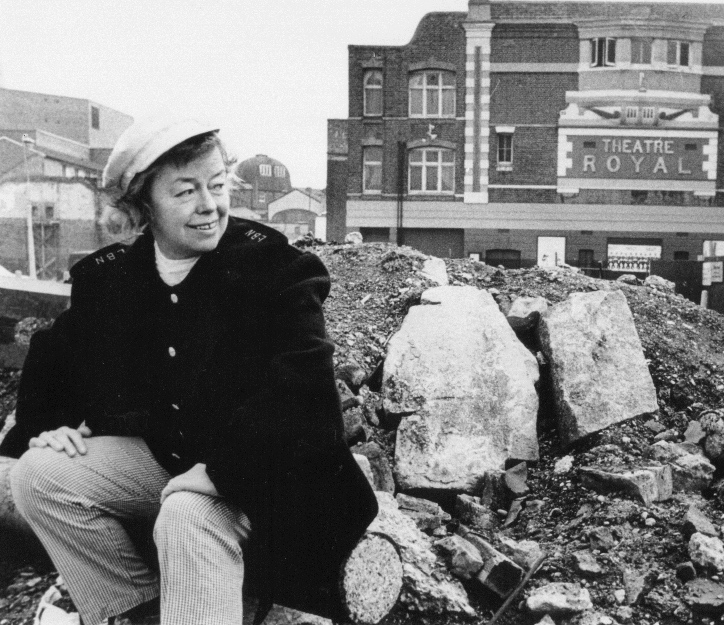

‘Fun Palace’ sounds very Sixties, but Joan Littlewood was no hippy: she belonged to an earlier generation. Born in 1914, she was making agitprop theatre in the 1930s and being sidelined by the BBC during the war for her communist sympathies. In 1953, she took over the empty Theatre Royal in East London, a poor district still marked by wartime bombing, and spent the next 20 years inventing an influential form of people’s theatre. In between directing plays and fighting over art and politics, Littlewood dreamed of a place where working people, like herself, could participate on their own terms in art, science, discovery, learning, pleasure. She imagined her Fun Palace as a building where you could:

‘Fun Palace’ sounds very Sixties, but Joan Littlewood was no hippy: she belonged to an earlier generation. Born in 1914, she was making agitprop theatre in the 1930s and being sidelined by the BBC during the war for her communist sympathies. In 1953, she took over the empty Theatre Royal in East London, a poor district still marked by wartime bombing, and spent the next 20 years inventing an influential form of people’s theatre. In between directing plays and fighting over art and politics, Littlewood dreamed of a place where working people, like herself, could participate on their own terms in art, science, discovery, learning, pleasure. She imagined her Fun Palace as a building where you could:

‘Choose what you want to do—or watch someone else doing it. Learn how to handle tools, paint, babies, machinery, or just listen to your favourite tune. Dance, talk or be lifted up to where you can see how other people make things work. Sit out over space with a drink and tune in to what’s happening elsewhere in the city. Try starting a riot or beginning a painting—or just lie back and stare at the sky.’

The socialist in Littlewood wanted everyone to benefit from Britain’s growing prosperity; the artist in her wanted them to be able to express their creative potential. Her vision drew on an ideal of the university and on elements of the music hall, science laboratory, pleasure garden, mechanics’ institute, adventure playground, art school and speakers’ corner.She called it The Fun Palace, and the phrase caught on—but it also caused difficulties. The idea was hard to explain, while fun is liable to raise hackles in utilitarian or Calvinist corners of the British psyche. She needed the support of politicians and planners but the Fun Palace sounded like an unworldly artist’s fantasy. Her friend and biographer, Peter Rankin, recalls that:

‘Joan, just by talking, could create the Palace before your eyes but soon she would be talking to people who would go away thinking: ‘What was all that about?’; and those were the people who would be giving planning permission and providing money.’

It didn’t help that Littlewood could be difficult to work with. Despite her commitment to the collective, she was not a team player. For years, she campaigned, made plans, raised funds, found sites, called meetings, urged, argued and coaxed: in vain. The closest she got were short-lived versions like Bubble City, a 1968 festival with an inflatable sculpture made by Action Space, and Stratford Fair, which happened in 1975 on waste land beside the Theatre Royal. Joan Littlewood died in 2002 with the Fun Palace designed for her by Cedric Price still a sketch on drafting paper.

That is probably a good thing. What Joan Littlewood had was an idea. If resources had been available to build the Fun Palace (which they might have been in France) it would have become an institution and everything exciting in it would have died. Her vision of creative and social freedom was incompatible with the obligations of property, law, staff and funding. The only attempt to create something like a Fun Palace—The Public in West Bromwich—failed principally because of this inescapable contradiction. But ideas are resilient. Forty years after Littlewood dropped it, another working-class theatre maker picked up her vision of the Fun Palace.

It happened in 2013, at Improbable’s Devoted and Disgruntled, annual Open Space on theatre. Stella Duffy, playwright and novelist, asked whether anyone present might be interested, as she was, in marking Littlewood’s centenary. From the conversations that followed came a proposal to invite people to host impromptu Fun Palaces on the weekend before Joan’s 100thbirthday on 6 October 2014. Three months later, she had been joined by Sarah-Jane Rawlings, an experienced producer, as co-director of a not-for-profit unincorporated association, lent a home by The Albany, an arts centre in south east London.

And the welcome implied by the word association has shaped everything that has happened since. Fun Palaces does not organise: it invites people to associate with an idea and with each other, for as long as they like, and for the reasons they have. Most of the people involved never meet except locally or online and only they decide what they will do and how successful it has been. A frequent Twitter-user, Stella began talking about the idea there, and among those who picked up the thread were many who had no professional interest in the arts or previous experience of organising events:

‘The people who made the Fun Palaces in Whitstable and in Farnham were following me for my books and they both asked me on Twitter “Can anyone do this?” We’re just going, yes, no idea, I don’t know, who knows? Yes… Then it became a thing.’

Her openness about the concept, and willingness to allow others to shape it, has become a defining characteristic of the new Fun Palaces and the most important reason for their success. Stella Duffy told people not only that she did not know what a Fun Palace should be, but also that she was not responsible for knowing. Unlike Littlewood, she did not want to be in control.

‘I’ve got much better at saying I don’t know, and believing that’s all right. What’s lovely about saying ‘I don’t know, why don’t you try?’ is that complete strangers are trying things and telling us what worked and what didn’t, so we’re getting all this knowledge we can pass on to others.’

The space she left has empowered others. There was no plan to follow, no instructions to conform with, just a belief that ‘everyone is an artist or a scientist’, a phrase of Littlewood’s that Stella and Sarah-Jane stumbled on when researching the original Fun Palace. It became the foundation of a manifesto:

We believe in the genius in everyone, that everyone is an artist and everyone a scientist, and that arts and sciences can change the world for the better. We believe we can do this together, locally, with radical fun—and that anyone, anywhere, can make a Fun Palace.

For Littlewood’s centenary in 2014, self-organising groups of volunteers made 138 temporary Fun Palaces in towns and cities across the UK. They used cultural and community spaces and invited visitors to try art, science and other creative activities. Each Fun Palace was different, because each place and each group of Makers (as the organisers are known) is unique. Some were stronger on art than science, or vice-versa; some were playful, others serious; some professional, others domestic. This diversity was seen as a strength and it has helped Fun Palaces achieve levels of participation that closely reflect the social make-up of the UK population. Whatever else they do, Fun Palaces involve people in ways and places that most cultural institutions have failed to do, despite their decades of effort.

There is an important reason why it was possible to go from nothing to 138 events in a matter of months. Fun Palaces values what people already do as much as what they might want to do next. As Sarah-Jane Rawlings says:

‘Fun Palaces are about recognising what is already happening, the unacknowledged cultural participation of people who often deny that they are creative at all. The Fun Palace shines the light on this artisting. It enables people to believe that the hats they knit, the models they build, the wood-whittling their father taught them and the Irish dancing in their bones, make them an artist—and an artist with something to share.’

Fun Palaces are not platforms for professional artists to share their skills and knowledge, although that can happen. They are social gatherings where non-professional but often gifted artists share their everyday creative work. That is why they can be self-organising and why, as the idea has spread, the numbers involved have grown so fast. In 2015, there were a similar number of events to the first year, but by 2017 the number of Fun Palaces had more than doubled, spreading to Germany, Norway, Australia, New Zealand and the USA. Over the October weekend, 362 Fun Palaces were organised by 13,750 people for 126,000 participants. An idea was becoming a movement.

So far, it has successfully resisted institutionalisation. Fun Palaces is enabled—it would be completely wrong to say managed—by the co-directors, two producers, an administrator and a marketing specialist, all part-time, for a total budget of £85,000 in 2016. Each event is planned, organised and supported within its community. How that happens depends on the people involved. In Farnham, Carine Osmont and Alex Mendonca, (who both work in the service industry) have led their campaign completely independently. It has been a tough but empowering experience, as Carine Osmont explains:

‘We are aware of our limits but making a Fun Palace encourages us to test them. It’s taught me to be honest and open about my experience and to face my own preconceptions and misconceptions—and those of others. I’ve learnt that we have to talk with the people who disagree with us to make changes. The campaign has given us permission to play, to take part, to engage. Someone who works in the arts told us two years ago we did not need that permission, but we do; we really do.’

Saying yes first and then working out how is the heart of Fun Palace’s success. Makers get guidance and advice, as much from each other as from the centre, and they adhere to some simple defining principles:

Free, Local, For all ages, Inclusive, Hands-on, Process as much as product, Yours, [and] Part of a Campaign.

Yours: this shared ownership, backed by the light and consistent support of Fun Palaces HQ, has empowered hundreds of thousands to have fun with Joan Littlewood’s belief that art and science should be—are—for everyone.

Defending fun

‘What’s happening a lot now is people saying—but what about quality? I can tell you what a good Fun Palace is, and a bad one, but I honestly don’t mind what they do. It’s up to them, not me.’

Some people find Littlewood’s belief that everyone is or can be an artist ridiculous. Addressing a presumably sympathetic audience at the 1979 Conservative Party conference, the novelist Kingsley Amis did not hold back:

‘It’s a traditional Lefty view, the belief that anybody can enjoy art, real art, in the same way that everybody is creative. In the words of that old idiot and very bad artist Eric Gill, “The artist is not a special kind of man; every man is a special kind of artist”. That’s only possible if making mud pies counts as art, which admittedly is beginning to happen.’

Through his blimpish satire, Amis was saying something more interesting than he probably intended. The special status of artists has been defended by the Enlightenment (and not least by artists themselves) but, like sainthood, insofar as it exists, the status of an artist can only be recognised by what they do. So beingan artist is the result of a sustained form of action in the world. If you do ‘artisting’ in sufficient quantity and, to a lesser extent, quality, the world will recognise you as an artist. The same is true of plumbers, crooks and accountants. Being comes from doing, and is only partly a matter of quality, which is why it is perfectly possibly to be an artist, but a mediocre one or even a very bad one.

To say that everyone can be an artist is not the same as saying that every artist’s work is equally worthwhile. The first is a fact; the second a judgement. But they are not incompatible. The world of sport has no difficulty with simultaneously supporting participation and excellence. Dennis Kimetto did something extraordinary when he broke the World Marathon Record at Berlin in 2014, but that did not diminish the personal achievement of the 28,945 people who completed the same course. He did not feel undermined by runners who crossed the line five hours after him. They, it is equally safe to say, will have found his run inspiring.

Why can this generosity not extend to the arts? Why do the people who have achieved so much, like Kingsley Amis, or who admire and support gifted artists in their work, like some arts managers, so readily disparage the efforts of those who do not reach so far. Do they see no truth in the sense of shared enterprise felt by amateur cellist Wayne Booth?

When Daniel Barenboim and I play chamber music it will never be in the same chamber, alas. Still, we are together in three essential respects: we are both makingmusic, not just listening to it; we are both often playing at the very same music, joining the same composers; and we are both eager to do it as well as we possibly can, with or without reward.

Like the community art movement which in many ways it resembles, Fun Palaces has met criticism from both sides of the political spectrum. For some it is another assault on standards, promoting the fallacy that art can be for all. For others it is an endorsement of a bland cultural inclusion that commodifies radical arts activism. Both perspectives share an oppressive certainty about what art is, how it should happen and what effect it has on people. Raymond Williams warned against such dogmatism 60 years ago:

A culture is common meanings, the product of a whole people, and offered individual meanings, the product of a man’s whole committed personal and social experience. It is stupid and arrogant to suppose that any of these meanings can in any way be prescribed; they are made by living, made and remade, in ways we cannot know in advance.

Cultural commissars ask ‘Is this art?’, confident that they know the answer. How much more interesting to ask ‘What is this art?’ Fun Palaces empower people to recognise and nurture the artist in themselves, not for a place on the winner’s podium but for crossing the line. They are comfortable with not knowing what makes good art, willing to suspend judgement and explore, listen and learn.

The photographs of workshops I took at Farnham are not very telling because what matters is below the surface activity. It is in the experience people have when they mould a piece of clay for the first time, or discover what oil pastel feels like, or see plastic cord soften with heat and become an expressive line, your line, that you drew. Such experiences cannot be shown, packaged or sold. They cannot be evaluated or reported. They can only be lived.

Community art accepts the intrinsic validity of people’s artistic experiences. They cannot be foreseen or controlled; and nor can their effects. A Fun Palace is not in children’s drawings or happy faces. It is not a fete or audience development. It is in discovering that you too can be an artist, and that no one else can be the artist you can be. That is an empowering experience, whatever people make of it. And sometimes it is one that needs to be fought for.

For the sources cited here, please download the PDF version of this case study.

With thanks to Stella Duffy, Alex Mendonca, Carine Osmont and Sarah-Jane Rawlings. Photographs by Helen Murray, courtesy Fun Palaces; except photographs of Farnham by François Matarasso